Election officials blast Trump's 'retreat' from protecting voting against foreign threats

Published in Political News

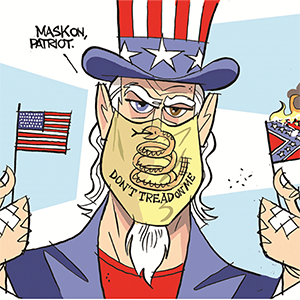

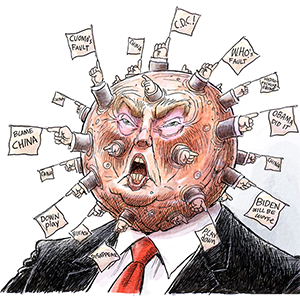

The Trump administration has begun dismantling the nation’s defenses against foreign interference in voting, a sweeping retreat that has alarmed state and local election officials.

The administration is shuttering the FBI’s Foreign Influence Task Force and last week cut more than 100 positions at the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. President Donald Trump signed the law creating the agency in 2018. Among its goals is including helping state and local officials protect voting systems.

Secretaries of state and municipal clerks fear those moves could expose voter registration databases and other critical election systems to hacking — and put the lives of election officials at risk.

In Pennsylvania, Republican Secretary of the Commonwealth Al Schmidt said states need federal help to safeguard elections from foreign and domestic bad actors.

“It is foolish and inefficient to think that states should each pursue this on their own,” he told Stateline. “The adversaries that we might encounter in Pennsylvania are very likely the same ones they’ll encounter in Michigan and Georgia and Arizona.”

Officials from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, known as CISA, and other federal agencies were notably absent from the National Association of Secretaries of State winter meeting in Washington, D.C., earlier this month. Those same federal partners have for the past seven years provided hacking testing of election systems, evaluated the physical security of election offices, and conducted exercises to prepare local officials for Election Day crises, among other services for states that wanted them.

But the Trump administration thinks those services have gone too far.

In a Feb. 5 memo, U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi said the administration is dismantling the FBI’s task force “to free resources to address more pressing priorities, and end risks of further weaponization and abuses of prosecutorial discretion.” The task force was launched in 2017 by then-FBI Director Christopher Wray, a Trump nominee.

In her confirmation hearing last month, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said CISA has “gotten far off-mission.” She added, “They’re using their resources in ways that was never intended.” While the agency should protect the nation’s critical infrastructure, its work combating disinformation was a step too far, she said.

This echoes the language from the conservative Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 document, which has driven much of the Trump administration’s policies. “The Left has weaponized [CISA] to censor speech and affect elections at the expense of securing the cyber domain and critical infrastructure,” it says.

But there is a direct correlation between pervasive election disinformation and political violence, election officials warn.

Federal officials led the investigations into the roughly 20 death threats that Colorado Democratic Secretary of State Jena Griswold has received over the past 18 months, Griswold said. Federal and Colorado officials also collaborated on social media disinformation and mass phishing scams.

“Trump is making it easier for foreign adversaries to attack our elections and our democracy,” Griswold said in an interview. “He incites all this violence, he has attacked our election system, and now he is using the federal government to weaken us.”

Colorado could turn to private vendors to, for example, probe systems to look for weaknesses, she said. But the state would be hard-pressed to duplicate the training, testing and intelligence of its federal partners.

Some election leaders aren’t worried, however.

“Kentucky has no scheduled elections in 2025, and we have no immediate concerns pending reorganization of this agency,” Republican Secretary of State Michael Adams told Stateline in an email.

Elections under attack

Since the Russian government interfered in the 2016 presidential campaign, the federal government has recognized that it overlooked security risks in the election system, said Derek Tisler, a counsel in the Elections and Government Program at the Brennan Center, a left-leaning pro-democracy institute.

Further, he said, the feds realized that election officials working in 10,000 local offices could not be frontline national security experts. On their own, local officials are incapable of addressing bigger security risks or spotting a coordinated attack across several states, Tisler said.

Much of the federal expertise and training came through CISA, Tisler said.

“Foreign interferers are not generally looking to interfere in Illinois’ elections or in Texas’ elections; they are looking to interfere in American elections,” he said. “A threat anywhere impacts all states. It’s important that information is not confined to state lines.”

During November’s presidential election, polling places in several states received bomb threats that were traced back to Russia. Ballot drop boxes in Oregon and Washington were lit on fire, and videos falsely depicting election workers destroying ballots circulated widely.

The fact that these attacks have not had a meaningful impact on the outcomes of elections may be due to the amount of preparation and training that came from federal assistance in recent years, said Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows, a Democrat.

Indeed, the right-leaning Foundation for Defense of Democracies praised the collaboration between federal and state and local partners on election security for dampening the impact of foreign interference in the presidential election, finding that adversaries did not “significantly” influence the results.

When Bellows took office in 2021, federal national security officials led state officials in emergency response training. After Bellows completed the training, she insisted that her state’s clerks, local emergency responders and law enforcement officers participate as well.

In addition, Maine coordinated with the FBI to provide de-escalation training to local clerks, to teach them how to prevent situations, such as a disruption from a belligerent voter, from getting out of hand. In 2022, CISA officials traveled to towns and cities across the state to assess the physical security of polling places and clerks’ offices.

Bellows said she’s most grateful for the federal help she got last year when she received a deluge of death threats, members of her family were doxed, and her home was swatted.

“I am deeply concerned that what is happening is actually gutting the election security infrastructure that exists and a tremendous amount of knowledge and expertise in the name of this political fight,” she told Stateline.

In Ingham County, Michigan, Clerk Barb Byrum last year invited two federal officials to come to her courthouse office southeast of Lansing to assess its physical security. Byrum got county funding to make improvements, including adding security cameras and a ballistic film on the windows of her office.

“The federal support is going to be missed,” she said. “It seems as though the Trump administration is doing everything it can to encourage foreign interference in our elections. We must remain vigilant.”

Scott McDonell, clerk for Dane County, Wisconsin, used to talk to Department of Homeland Security officials frequently to identify cybersecurity threats, including vulnerabilities in certain software or alerts about other attacks throughout the country. Losing that support could incentivize more interference, he said.

“I think it’s a terrible idea,” he said. “How can you expect someone like me, here in Dane County, to be able to deal with something like that?”

States fill the gap

Local election officials are nervous and uncertain about the federal election security cuts, said Pamela Smith, president and CEO of Verified Voting, a nonprofit that works with state and local election officials to keep voting systems secure.

The threat landscape for elections is “extreme,” she said. And even though it’s not a major election year, quieter times are when election offices can prepare and perfect their practices, she said.

“It is a retreat and it’s a really ill-advised one,” she said. “It’s a little bit like saying the bank has a slow day on Tuesday, we’re going to let our security guards go home.”

With a federal exodus, there will be a real need for states to offer these sorts of programs and assistance, said Tammy Patrick, chief programs officer at the National Association of Election Officials, which trains and supports local officials.

“There’s going to be a big gap there for the states to try and fill,” she said. “Some of them might be sophisticated enough to be able to do some of it, but I think there’s going to be some real disparate application across the country of who’s going to be able to fill in those gaps.”

Bill Ekblad, Minnesota’s election security navigator, has leaned on the feds to learn the ropes of election security and potential threats, help him assist local election offices with better cyber practices and keep officials throughout the state updated with the latest phishing attempts.

He finds it disheartening to see the federal government stepping back, and worries that he won’t have access to intelligence about foreign threats. But after five years of working with the federal government, he is hopeful that his state has built resiliency.

“We have come a long way,” he said. “We will be able to move forward with or without the partnerships we’ve enjoyed in the past.”

©2025 States Newsroom. Visit at stateline.org. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments