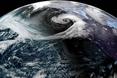

Atmospheric river meets bomb cyclone: The result is like a fire hose flailing out of control

Published in Science & Technology News

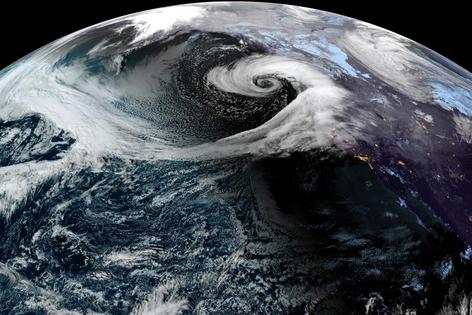

The West Coast’s rainy season has arrived in force, as an atmospheric river carrying moisture from the tropics joins a bomb cyclone off the Pacific Northwest coast. Heavy, wet snow began falling in the mountains on Nov. 19, 2024, and bursts of rain have been blasting the Oregon and Northern California coasts. These storms are forecast to last for days, hitting up and down the West Coast. Parts of Washington have seen more than 70 mph winds from the bomb cyclone.

When these two phenomena get together, the weather gets hard to predict, as meteorologist Chad Hecht of the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at the University of California San Diego explains.

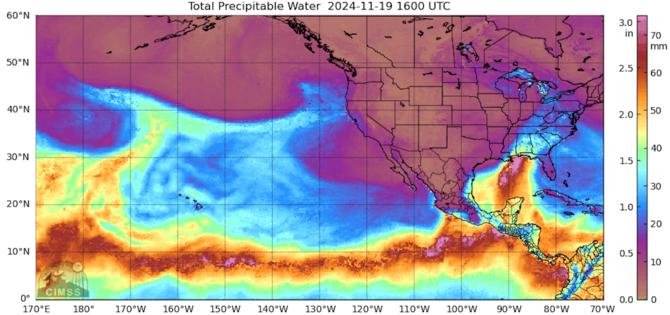

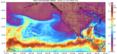

An atmospheric river is exactly what it sounds like – it’s a long, narrow river of water vapor in the lower atmosphere. These rivers in the sky transport moisture from the subtropics to the mid-latitudes.

When an atmospheric river runs up against North America’s West Coast, the mountains and complex topography force the air to rise, cool, and the moisture to condense and precipitate. That can mean feet of snow at high elevations and rainfall elsewhere.

That’s not always a bad thing. Weaker atmospheric rivers help replenish reservoirs that are essential for supplying water during the dry season. California relies on atmospheric rivers for up to half of its yearly precipitation and streamflow.

This storm, however, is expected to be stronger and more unpredictable than unusual because of the bomb cyclone.

Atmospheric rivers tend to form out ahead of cold fronts that are associated with low-pressure systems known as extratropical cyclones. These are air mass boundaries circulating around the area of low pressure. A bomb cyclone is a rapidly intensifying extratropical cyclone.

These two weather phenomena go hand in hand. A strong atmospheric river will feed moisture into the low-pressure system, providing fuel for the cyclone. The stronger the low-pressure system becomes, the stronger the atmospheric river becomes.

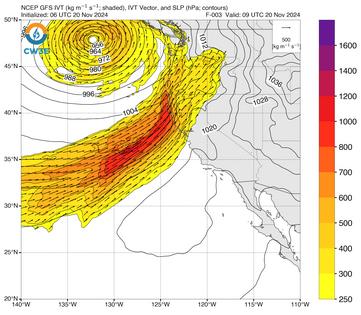

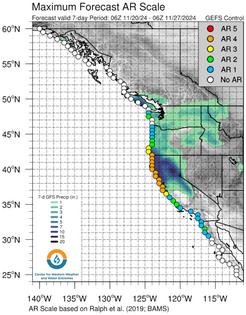

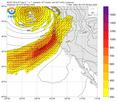

This atmospheric river is impressive for its duration – it is forecast to continue hitting the coast with moisture for several days and may spread precipitation as far south as Southern California. Its integrated vapor transport – a measure of how much moisture is moving in the atmosphere – suggests that we’ll see a lot of rain and snowfall, with over a foot of precipitation expected in some areas.

On top of that, the bomb cyclone – one of the strongest we’ve seen along the coast – is bringing powerful winds.

While the atmospheric river is hitting the coast, the bomb cyclone will sit over the ocean off the Pacific Northwest and spin. As it spins, it sends small frontal waves through the atmosphere that push the atmospheric river inland. That creates a lot of uncertainty for forecasts.

If you picture the atmospheric river as a fire hose pointed at the coast, these frontal waves are essentially the fireman taking his hands off the fire hose and letting it go all wavy. It can move northward, and then back southward. The question is how far it will go before pivoting, then how quickly it will pivot back.

So, how long specific parts of the coast will see rainfall and how intense that rainfall will be are the big questions.

The harder and longer it rains, the more impacts you’re likely to see.

The saving grace with this storm is that it’s early in the season, so the soils are relatively dry. That means they’ll be able to soak up more of the moisture. If a storm like this hit in winter, after the soils were already saturated, more water would run off, causing more widespread flooding than an early-season storm.

With a storm this intense, the main concern in areas recently burned by wildfires is high-intensity precipitation.

When land burns, the surface can become impervious – almost hydrophobic. So, when that surface gets hit with high-intensity precipitation, the water runs off a lot faster than if vegetation or soil was able to absorb the water. Wildfire burn scars tend to be in hilly places, so that can lead to debris flows.

It’s really a matter of chance whether the burn scars get that intense precipitation. A strong cold front can form narrow cold-frontal rain bands that bring bursts of high-intensity rain. These small but powerful rain bands tend to form in dynamically robust storms. Meteorologists are seeing some signatures suggesting that these features could form.

The best advice if you’re in one of those areas is to pay attention to the National Weather Service’s watches and warnings.

Unfortunately, one really impressive storm doesn’t tell us anything about what’s ahead.

We’ve seen seasons with powerful early-season storms and then not much more. October 2021 is an example: A really strong storm hit that month, with record-breaking, 24-hour precipitation accumulations. But then the tap shut off, and California ended up with below-normal rainfall for the rest of the year.

There are tools that offer some indication of whether the season will be above or below normal, but those aren’t 100% accurate.

For example, the La Niña weather pattern that’s close to forming in the Pacific typically indicates drier than normal conditions across California. But looking at the past 10 years, we’ve had some really wet La Niñas – 2017 being the granddaddy of them all, with record-breaking precipitation in the northern Sierra.

Meteorologists typically have a good sense of what’s coming in the short term, about 10 days out. But what the rest of the season will look like is really an educated guess at this point.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Chad Hecht, University of California, San Diego

Read more:

Atmospheric rivers are shifting poleward, reshaping global weather patterns

What is an atmospheric river? With flooding and mudslides in California, a hydrologist explains the good and bad of these storms and how they’re changing

Atmospheric rivers are hitting the Arctic more often, and increasingly melting its sea ice

Chad Hecht receives funding from California Department of Water Resources, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Sonoma Water, Yuba Water Agency, & Orange County Water District.

Comments