Two-thirds of Silicon Valley tech workers are foreign-born, new report reveals

Published in Business News

SAN JOSE, California — It’s no secret that the skills and labor of workers from other countries helps fuel Silicon Valley’s innovation, but a new report has put a number to it: 66% of technology workers in the region are foreign born, according to the 2025 Silicon Valley Index produced by think tank Joint Venture Silicon Valley.

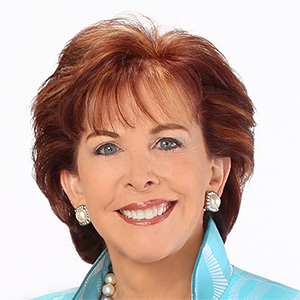

“I think it does surprise a lot of people,” said Russ Hancock, Joint Venture’s CEO. “What we easily forget is that Silicon Valley is not an American phenomenon — it’s an international phenomenon. Silicon Valley was built by the best and the brightest coming from all quarters. Communities that draw on the whole world are communities that thrive.”

Venture capitalist Anis Uzzaman, CEO of San Jose-based Pegasus Tech Ventures and chair of the annual Startup World Cup, said foreign-born tech workers provide “key ingredients” for Silicon Valley startups and established companies.

“They bring diverse perspectives, world-class talent, unique problem-solving approaches, and global market insights,” Uzzaman said.

The proportion of tech workers who are foreign born is substantially higher than the percentage of foreign-born Silicon Valley residents, which hit a record high of 41% in 2023, Joint Venture reported.

Of tech workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher, 23% came from India and 18% from China, while 17% were born in California, according to the index.

The Valley’s reputation as the world’s leading technology hub and “a place where breakthrough things happen” plays a powerful role in drawing talent from around the globe, said Sean Randolph, senior director of the Economic Institute at the Bay Area Council, which represents businesses including major Silicon Valley tech companies Google, Meta and Apple.

“A lot of people want to be a part of that,” Randolph said.

Many come to Silicon Valley chasing opportunities not available in their home countries, said Pratima Joglekar of Fremont, a former advocate for foreign workers on visas.

“You study in the U.S. and then you try to work for one of the big companies or you try to do your own startup and sell it or get it acquired by a bigger company,” said Joglekar, 40, who works in a law firm and is married to an India-born software engineer employed as a manager at Google. “That’s the dream.”

Foreign workers enter the region “through multiple windows,” Randolph said.

“There’s a very large number of incubators, accelerators and facilitating organizations here in the region whose primary purpose is to connect entrepreneurs from other countries into the innovation system here,” Randolph said.

Many Bay Area tech companies are multinational and transfer foreign workers into their local offices, Randolph added.

India-born systems analyst Mebi Babu was transferred in 2010 with her husband by their Ireland-headquartered employer from India to Illinois. The company moved them to Pleasanton, California, in 2015, and in 2020 she took her current job with Santa Clara County.

“I feel blessed,” said Babu, of San Ramon. “There were a lot more opportunities here that I could explore.”

High-profile universities — notably the University of California-Berkeley and Stanford University — draw foreign college students to study science, technology, engineering and math, many with an eye to getting jobs in the valley after graduation. The number of science and engineering degrees conferred annually by Bay Area universities has grown 117% since 2002, with more than 21,500 science and engineering degrees earned locally in 2023. That’s still far from enough to meet the needs of the tech industry, which created jobs that outstripped degrees from Bay Area schools by more than 20,000 from 2019 to 2023, Joint Venture reported.

“If you look at the quality of educational programs in California or the United States, the skills level of people coming out of high school just in math, it’s not there,” Randolph said. “The system as a whole is just not producing the number and quality of graduates that the technology community needs. If it did, they’d be hired.”

Abundant venture capital — $69 billion invested in Silicon Valley and San Francisco in 2024, according to the index — adds another enticement for startup founders and budding entrepreneurs from around the world, who need funding to pursue their innovation dreams, Hancock said.

Some 45% of Bay Area tech startups are founded by people from other countries, with a substantial number launching their companies after graduating from U.S. universities, according to research by the Bay Area Council. Many foreign founders start at established tech companies in the region, Randolph said.

More than half of America’s most highly valued tech companies were launched by immigrants or children of immigrants, including Apple, Google, Meta, Intel, Cisco, Oracle, Netfix and NVIDIA, according to the 2018 Internet Trends Report by tech forecaster Mary Meeker.

The H-1B visa, intended for workers with specialized skills, has facilitated inflow of foreign workers. While Silicon Valley’s tech industry lobbies to increase the annual 85,000 cap on new visas, arguing that the H-1B allows them to secure the world’s top talent, critics point to the dominant use of the visa by staffing companies found in the past to be paying less than prevailing wages, and supplying thousands of workers to Silicon Valley firms.

John Miano, a lawyer representing U.S. tech workers in a long-running lawsuit now asking the U.S. Supreme Court to ban non-Congressionally approved work permits for spouses of H-1B workers, said educating American kids in STEM was supposed to reduce the need for foreign tech employees. However, because of the H-1B, “We doubled the number of computer science graduates and now they can’t find jobs,” Miano said. “America has lost control of its technology labor supply chain.”

Whether a shortage of U.S. tech workers exists has been hotly debated for years, with no conclusive data to support either side of the argument.

Native-born talent on its own cannot meet the industry’s needs, Uzzaman said. “We’re consistently short in specialized areas like AI, cybersecurity, and advanced software engineering, often by thousands of skilled professionals annually,” Uzzaman said. “Immigration isn’t a replacement, but a complement to native-born talent. Both are needed to maintain Silicon Valley’s role as a global innovation hub.”

©#YR@ MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit at mercurynews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments